Here, in Parma, after listening carefully to my stories about traveling in Europe, my hostess Patrizia suggested that I spend at least part of the day with Laura. I agreed. And so most of what you'll read for today will be about food. Not so much the consumption of it, but the art of producing some of this region's culinary treasures, as seen through the expert eyes of someone who knows this side of Parma inside out.

As she brings down my early tray of food, Patrizia says -- there's fog. It's magic!

I appreciate her upbeat tone, really I do, but I tell her that I've known nothing but fog since I came here and though I agree that it's pretty, I feel a little like a I do after a long winter in Wisconsin. I wish I could at least catch a glimpse of spring. Or in this case -- sunshine.

She is not to be put off: magic! Truly, everything is just that much more beautiful!

And then she serves me an elegant breakfast, agreed upon the day before, because I do not want more food than I will eat and so it is the perfect breakfast with everything that I love...

But I eat it in a hurry. Laura is picking me up at 9.

Who is Laura -- you ask. Well, she is an enterprising young woman, born and raised in Parma and she is starting to do what I once tried to do with my Field to Table project of some dozen years back: she wants to show off the family and in one case the cooperative producers of local foods. She'll be taking me to three different places, all just outside of Parma: La Traversetolese -- makers or Parmiggiano Reggiano cheese, then the family Conti -- curers of Parma prosciutto (a mother and daughters operation), and finally Picci Acetaia -- the Balsamic House of the Picci family (a father and son affair).

Not interested in finding out about what makes this part of Italy hum? I can't even imagine that possibility. You can't just sprinkle cheese on your spaghetti and fake balsamic vinegar on your salad without knowing about what you're really doing or eating. It's not all that it appears to be!

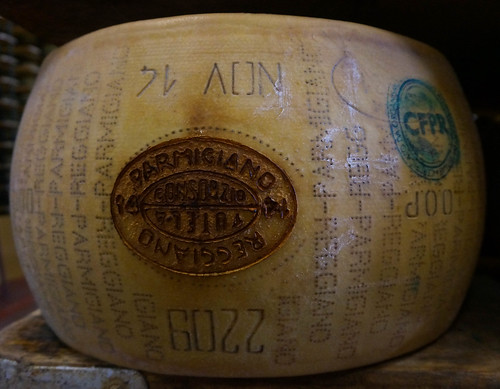

Parmigiano Reggiano

We drive through a misty landscape. In the distance, I see hills. The Apennines -- Laura reminds me. Beyond them there is the sea and Cinque Terre.

We're on our way to just one cooperative, where 1000 cows belonging to fewer than a dozen farmers, give milk to make just 38 wheels of Parmiggiano Reggiano cheese daily. (600 liters of milk gives you one wheel of cheese which, after aging, weighs about 40 kilo.) Every day. No days off for the cows and thus for the workers. Christmas included.

Now, to you it's all Parmesan cheese. Herein lies the problem. Italians eat their Parmigiano Reggiano in huge amounts. Too, they export it: to France, to Germany and third on the list -- to the US. But Americans buy Parmesan cheese (a generic term), look at a picture of an Italian flag or the leaning tower of Pisa on the package and think -- I'm eating the real thing! And sometimes they'll also think -- what's all the fuss, this stuff isn't so hot.

That's because the American agencies will allow the misleading labeling practice to sail forth. It's a generic term! Let them think they're eating the real thing!

This makes the Consortium of Parmigiano Reggiano producers very upset. Why? Because they are so damn proud of their product and they want you to know which one is the real thing and which one is a knock off.

Laura didn't tell me this. It's an old story that has been making local producers mad ever since someone packaged some sweet grape juice, gave it some fizz and called it champagne, making the real Champagne producers fizz with with discontent.

We put on protective clothing and we enter the cheese making facility of Traversetolese.

Oh, the fragrance! Milky whey, bathing the curds that are then shaped into wheels of cheese.

We watch for a long time. I wont go through the process here. You have to go see this yourself. (Get Laura to take you: you can't just enter on your own. She has special permission.)

In addition to the Parmiggiano Regiano (THE official Parmesan cheese), this facility also makes a small batch Grand Special: flax seed is used in the production of it, adding omega 3 to the cheese. Too, it's less salty -- overall, a healthier addition, to meet a new demand for this kind of product. (I did not know that actually even the real Parmiggiano Reggiano is a healthier version of cheese -- it's made with partially skimmed milk and so the fat content is a remarkably low 26%).

I tasted the Gran Special -- it's good! Laura said there's a vegetarian version too and there's talk of a kosher cheese. I joked that there should be a lactose free one, but she reminded me that actually an aged cheese is pretty much lactose free after 30 months.

Oh, such beautiful cheeses they are! With strict standards of quality control: testing, pounding, retesting, scrapping some that doesn't come up to snuff. But when there is that label, it says it all: this is the stamp of the real thing.

Laura pours me a bit of local Malvasia wine for my cheese tasting.

And I'm asked if I want some cheese to take home. But which one?? There's the young cheese (aged a minimum 12 months), the medium aged at 24-30 months, and the 36 month cheese. Laura says -- oh, it depends on your use: you'd want the medium for your tortelli erbetta - you know, pasta stuffed with cheese and swiss chard. But the 36 month old one if you're making the stuffed capeletti with meat in broth.

Well now.

I pick up some of the medium aged because it crosses over from an appetizer (with acacia honey -- yum!) to a pasta dish. So cheap here! So pricey (and who knows how authentic) back home.

Prosciutto di Parma

We're back in the car, leaving the cooperative and I note that an incredible thing has happened: the fog has lifted! Completely, totally!

We're driving up into the hills, past castles and vineyards...

... up, up to visit the family run Cotti Prosciutto making facility.

All of the Prosciutto di Parma is made in the hills, Laura tells me. (She knows a hell of a lot about this stuff!) It's a very important requirement: the windows are always long and tall and they are opened in good weather so that the air comes in -- sea air that's purified over the mountains so that it is of the sea, but crisp and very special. It is what makes this prosciutto so great!

Prosciutto itself is not a protected term - it refers to the cured meat that comes off the hind leg of a pig. But there are two prosciuttos that are protected: one that is cured in this region of Parma (in which case it is Prosciutto di Parma), and the other which is cured in San Daniele (in the Venezia Friuli region and of course, then it is Prosciutto di San Daniele).

Which is better? I have to ask. This, of a woman from Parma.

She answers honestly: San Daniele is pressed and so it has less moisture and is more salty. Parma is the sweetest. We use only salt from Sicily - no other spices. In Italy though, 40% of all prosciutto is made in Parma and 13 % in San Daniele. Parma alone account for some 9 million hams per year. (There are 160 produces of prosciutto here.)

That's huge!

Well, it's going down. People now start to eat less because there is a retreat from red meats.

In the States we call pork "the other white meat." It's all in the advertising. She laughs.

The Conti business was started by two brothers -- both farmers -- in 1969. They both died, but the wife of one and her three daughters carry on.

I learn a lot about the pigs -- where they come from, what they eat, what breeds are used. This is tougher for me, especially when I learn that they are slaughtered at just 9 months (they don't grow after that, having reached their optimal 170 kilo). Still, I am not a vegetarian and so I can't be hypocritical here. And I know these pigs were well cared for before they made it to the local Prosciutteria (a store that sells only... prosciutto).

An interesting part of the process comes after the salting and initial aging. These two rub in suet and if you think this is easy and you could do it with your eyes closed, think again. These guys are professionals -- they've studied their trade since they were 15 years old. They know how to rub less on the veins, how to move their fingers deftly over parts of the meat.

Okay -- the finished product, ready for more aging. A total of 24 months, on wooden racks for the aroma, under tight quality and sanitary controls, because it's the EU.

The stamp of approval:

We, by the way, import a lot of Parma prosciutto but we refuse to take any unless it's been inspected by our own vets. And we insist that the prosciutto producers pay for all our vets' travel expenses, meals included. Clever, no?

So, where is the market for this meat? 70% is consumed by Italians. Then US, then France, then Germany and the UK.

Michela, the youngest sister, prepares a plate for me to taste.

I tell her -- it's too much! Please do not be insulted but I wont be able to finish it! She smiles and nods her head and pours me some more of that same fizzy Malvasia local wine.

And of course, I eat the whole thing. It's lip smacking good!

And the view from the Conti production facility -- sublime.

Traditional Reggio-Emilia Balsamic

You know, when you eat in cheap places around the States these days, you very often get your salad with "balsamic dressing." And it's awful. Ed has always said he likes the taste, but I've been skeptical. I've obviously purchased "balsamic vinegar" for my own kitchen. And I thought I was so clever -- I picked up only the stuff that says "made in Modena." And still, often times it has left me unimpressed.

I think today I finally understood what the problem is.

It turns out that there are three vinegars that are allowed to use that term "balsamic."

There is the IGP Modena Balsamic that you will find in every grocery store across the world.

There is the PDO Traditional Modena Balsamic.

And there is the PDO Traditional Reggio Emilia Balsamic.

What you and I purchase is the first. It is allowed to sport the label "made in Modena" if any one of the production components comes from Modena. A grape comes from the region? That's enough! Caramel color added there? Fine! Made in Modena! Even though it can really be made in Greece. Or anywhere else. You see the problem. There is no consistency. If you buy and use a balsamic vinegar ("made in Modena") that you think is sort of okay, stick with it because another one may be awful.

We cross the river that separates the Parma region from Emilia-Romagna (if we drove further, we'd be in Modena). In the small village of Cavriago, we pull up to the Bicci Acetaia, where Marco has basically taken over his father's business of producing the Traditional Reggio Emilia Balsamic.

If there are no controls over the IGP Modena Balsamic, the Traditional vinegars more than make up for it! Everything has to come from the given region: the grapes, the cooking of the must -- grapes, seeds, stems -- slowly, for 36 hours, no boil! And of course, the aging: in barrels of five types of wood (chestnut, oak, cherry, mulberry, juniper), for at least 12 years and so on and so on. Makes my head spin.

We look at the rows of barrels up in the "attic" -- this is where they're aged and moved. No air conditioning or heating allowed. It must be done in the changing temperatures of the seasons. Why? Because, that's the way it has always been done.

I thought initially that this work wasn't too hard once you put the stuff in the barrels. Sit and wait. But no. The moving, the rotating, the preserving, bottling -- all for a superb vinegar. No wonder they're mad that people use crap and call it Balsamic from Modena.

So where does this Traditional good stuff go? Italy. Canada. Japan. Russia.

Russia? I ask, surprised. Marco laughs. There are certain people in Russia who have too much money on their hands. And there is the embargo of European goods. So they come here, they buy a bottle for 40Euro (that's the least expensive one!) and they sell it to their rich friends for 400.

I'm shocked France isn't on the list.

I'm not. He tells me. Mediterranean countries don't rush toward this stuff. It fits especially well with northern European cuisine. In France, they use it in Alsatian cooking but not so much in the southern provinces. (His father also ran a "Balsamic vinegar" restaurant before he retired. They know a lot about food and vinegar pairings.)

I do buy something. For a holiday present. Can't say what or why. But it will come with my instructions: do NOT just sprinkle this stuff on your salad. Put just a drop over a chunk of Parmiggiano Reggiano... or stuffed pasta, after you've doused it with the cheese...

Driving back to town, Laura and I switch topics. Away from food (sort of), toward families. I know she is close to hers. I know that Patrizia is close to her mom and dad. I comment that in the States, families often live far apart and the relationship between mother and grown daughter is the topic of much discussion, often not the most honorable kind. Laura nods her head -- we've noticed this in American movies. Every time a woman's mother calls, the woman rolls her eyes, like this. She demonstrates, not inaccurately. Ah, what people pick up about us!

It's after two when I am finally back at the b&b. I think I should take a walk, what with the sun and the warmer temps, but by the time I set out, the fog is rolling back in and the temps plummet to near freezing again. I go across town, past the art museum that I'm quickly running out of time to see...

... across the river, which Bertolucci mocked (quote snitched from Wiki): "As a capital city it had to have a river. As a little capital it received a stream, which is often dry."

... to the park. But rather than strolling leisurely...

... I take a short cut (as do others -- it's rather empty!)...

... and head back to town.

At least when I enter children's clothing stores, I warm up for a few minutes.

(admiring, contemplating...)

In the evening, I tell Patrizia about my day. We talk about inn keeping, about food. She tells me exactly what I should order tonight when I go to one of her favorite places in town (Trattoria del Tribunale).

Get the the tortelli (stuffed pasta), but ask for a combination, so you can try them all-- especially the one with cheese and chard, and the one with pumpkin and the one with potato. And after -- either the horse meat, raw or cooked, or the veal with potatoes. Oh, and you have to start with the fried bread and prosciutto.

I protest. I can't eat all that.

She thinks for a bit. Ask for a half portion of the fried bread and prosciutto.

I step out into the now denser fog...

... and head for the trattoria.

I eat the bread, the prosciutto, the four kinds of tortelli.

And the veal (I'll save the raw horse meat for another time...) and I even throw in a salad because I miss the raw veggies.

I do have a tinge of guilt. Not because it's so much food, but because I am eating a young pig (prosciutto) and a young calf (veal). I had told myself that I draw the line at eating animals that don't quite reach adulthood. Still, I'm doing it for my host and I must eat as the Parmiggiani eat, because otherwise it's unfair, right?

And of course, it is the best meal I have had on this trip.

P.S. It cannot be said that the Italians do not have a sense of humor. This, from the person at the table next to mine:

As I walk home, I see that the bars are spilling out onto the streets. No one seems to notice that it is foggy and near freezing.

Frankly, I'm not noticing much of it either. It's magic. Truly magic.

You had me looking in my fridge and cupboard at my cheese and balsamic. I also draw the line at eating baby animals and had to break it recently to not offend the host. =/

ReplyDelete