My American friends came to Poland for many reasons, but perhaps the real impetus for the trip was Shmuel's great desire to see the village of Przedecz, where his father grew up until, in 1936, at the age of 21, he emigrated to Palestine (most every one else who stayed behind perished at the hands of the Nazis).

I offered to take Shmuel and Barbara to Przedecz -- a two hour drive west of Warsaw -- but I worried about the trip. Traffic on that route is horrendous. We'd have to rent a car. All this and for what? I know from Google maps that Przedecz looked like any other provincial village in Poland: a place where nearly everyone is poor and living in drab post war housing. Where in this will Shmuel find what he is looking for?

I shared my worries with my Polish friends and at once one of them volunteered to go there with us.

And so on a gray day, with a steady threat of rain, right after my breakfast...

... my Polish friend drove up and we climbed into her car and set out.

At first, I thought that, by some weird twist of fate, we hit the highways twisting around L.A. instead of Warsaw. Since when do we have such terrible congestion here??

Elka, my Polish friend, is unperturbed. Weaving between endless trucks and no fewer cars? No problem! (She did remind me that this is the beginning of a very difficult -- travel wise -- weekend in Poland, as the country is getting ready to observe All Saints' Day next Tuesday and everyone is on the road. In other words, I picked a lousy time to be doing a long distance trip.)

Finally, we pull into Przedecz. Where to now?

Shmuel has an address where his grandparents most likely lived. I was wrong to think it would be gone: an old house, a clearly old old house is still standing there, stuck in this block, right off the square.

We're brave. We knock on doors at the given address.

Nothing.

Undaunted, we go inside.

We follow an entryway to the courtyard. My, but everything looks old here!

It's so odd -- Przedecz hasn't many prewar houses left standing, but this one -- this home that likely was Shmuel's father's home (and now is the home to the granddaughter of the man who moved in just at the end the war) is still here. So is the stable -- now used as a carpenter's workshop. We learn from two workmen that the owners have a coffin making business here.

Emboldened, I ask the older men gossiping outside the grocery store about the people who live there now.

It's the big woman. The granddaughter.

And is the grandfather still alive?

Oh yes. Over in the yellow house.

Do you know anything about the family who lived there before the war?

No... we're from the village outside here. Lady, that was 60 years ago!

Well, maybe a tad more, but okay. My worst fears realized: no one knows anything. Shmuel will go home home disappointed.

(Village square)

We walk over to the "yellow house." No one answers the knock.

And then to the old castle grounds. I'm thinking -- maybe it will bring Shmuel some solace to learn of the history of some of the buildings that were here at his family's time.

There is a notice board and I translate a little of the history of the castle: fortified, fighting off invasions, burned, reconstructed, eventually occupied by the Germans...

Just across the street, there is a small building with a buggy outside and a plaque by the door.

We walk there now. It's the Regional Museum of Przedecz. Locked.

Wait, there is a sign that says it's open until the end of October (we're in!) until 4 p.m. (yes!).

Except that it's locked.

I find the old stairs that lead upstairs. Someone is living here. Where am I?? (I later learn that the building is divided into several rooms for rent. The one that now houses the museum, had been used by a fellow who couldn't pay his rent. So they shut off his electricity. There still is no light in the museum.)

On the museum door, there is a posting which includes a phone number. Elka dials it on her phone. Adam, the apprentice curator, picks up, then, learning that there is actually a potential visitor to the museum (a rare event), rushes over with the key.

Inside, there are the artifacts of daily life in Przedecz.

Well now, this is better! An ethnography of the village!

We're just getting it started, says the very young and enthusiastic Adam (I translate).

We still have to get the electricity running again!

(Adam and Elka, in discussion.)

Adam is terribly curious what brings us to Przedecz. We learn later that Shmuel and Barbara are the first foreign guests he's had here. When I explain, he asks --

what was Shmuel's father's last name?

When he hears it, he frowns.

I'm sure I've seen it somewhere. (Mind you, if Adam is even 30, I'd be surprised.)

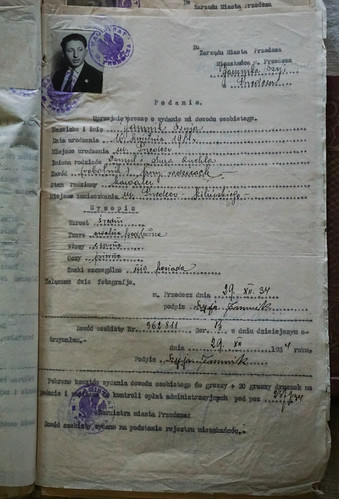

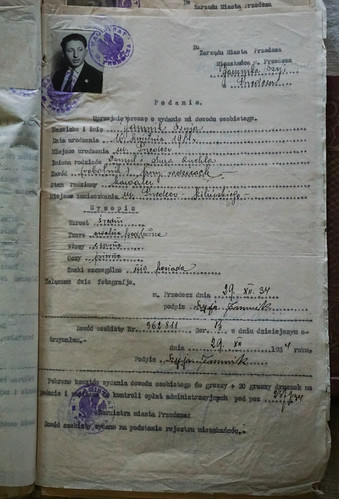

He opens an old cupboard and digs out a book that clips together faded sheets of paper. I mean, really faded and crumbling sheets of paper.

This is a compilation of people -- Jews, Christians, anybody -- who applied for a personal i.d. before the war. It's not well organized and many (most?) of the pages are missing.

What's a personal i.d.? -- Shmuel asks.

Ha! The same i.d. I had to apply for when I reclaimed my Polish citizenship! Every Pole has one.

There are maybe 100 crumbling sheets of paper with attached photos in the folder. Adam flips through them. He's so sure he remembers the name.

100 sheets of paper.... So few? How many had actually filed papers here in those decades? Thousands? 2000 people lived in Przedecz just before the war. 800 Jews. What are the chances that we can find anything at all?

As we approach the end of the stack, I just want this to be over! We had never expected a specific reference to Shmuel's family. But, Adam had raised our hopes. And now we're going to be disappointed.

And then ... there it is!

What are the chances? Of the many many members of Shmuel's family, only his father's papers remain.

It just stopped us cold. It's as if this man, this young man had stepped into the room and shared his story with us:

[This is from my own summary of all that I learned today and from Shmuel's account of his conversations with his father, which he has given me permission to share]:

I applied for an ID in the year 1934. All was okay. I experienced discrimination, but yes, all was okay. I loved my childhood in Poland. When I do the dishes, I still sing the Polish songs that I remember from those years. But I had to leave.

We walk out into the damp, chilly day. Adam wants to show us the castle and he wants us to hear the corrected history of its last few centuries.

With his special key, he leads us up to the tower -- this is the part that remains intact. 600 years and it survived everything! Out of one window, you can see the gray house where Shmuel's family lived.

In this high old tower, we linger. And we talk.

Adam has a deep fascination with history, even as he has decided to pursue a certification in fire control. (In other words, he wants to be a fire fighter.) I ask him how long his family has lived in his town.

I traced our roots here to the 17th century!

Shmuel asks (via my interpretation) --

Did they teach you in school about the history of what happened here? [After all, Przedecz was one third Jewish before the war and zero percent Jewish thereafter.]

Oh yes, we spent many days on it!

Pause...

Of course, not all of it...

I ask --

what part do you think was missing?

He tells us that not everyone is happy to talk about the past.

We know this story too well, of course. At a time of war, of fear -- some perform heroic acts, others do the opposite. It's no different here, in Przedecz. The Jews were forced by the Germans to live in a village ghetto and eventually they were gathered and held hostage under horrific conditions. After -- labor camps, death camps... Some Poles took great personal risks to help the Jews who managed to escape, others assisted the Gestapo, ostensibly to protect their own skin. I imagine those are the people who do not want to remember what happened then.

We say good bye. Adam is an extraordinary young man and it is really thanks to him that this story continues to be written, discussed, remembered.

Elka leads the way to the place where there was once a Jewish cemetery. Early on, the Germans who occupied Przedecz, ripped out the tombstones from the ground and threw them into the lake. Adam told us that a half dozen had been hidden and preserved, but at the moment, there is nothing here but a commemorative plaque, put there by a family member of a Jewish person who wanted to honor all those who were buried here.

It's raining now. My American friends live in New Mexico and they have 310 of sunshine there each year, but in Poland, they've had mostly rain. I tell them --

this isn't a visit that asks for sunshine. Those who lived here endured rain in October. We are mourning them now...

In our stroll through this village, talk inevitably turns to what it was like to live here (in Przedecz, in Warsaw) under communism. Elka and I share memories and they are not dissimilar -- I've known her since my high school years. In trying to put things into context, she comes forth with an old saying we had --

In the camp of Eastern Europe, ours -- Poland -- was the happiest barrack.

So true. We were happy kids, turning into adults. I feared my boyfriend didn't love me and that I was too much of a tomboy, but I loved my childhood. Just as Shmuel's father loved his.

In Warsaw, Elka goes off to attend to a car problem and my friends and I search out supper. I take them to Zorza. We eat cabbage stuffed with buckwheat and mushrooms.

Day is done

Gone the sun

But the spirit stays strong.